Another Giant Gone: Gene Yahvah, 1926-2023

Gene Yahvah died in Libby, Montana on May 23, 2023, his ninety-seventh birthday. He was a legend among Montana foresters

Keynote address by James D. Petersen

Founder and President, The Evergreen Foundation

Resilient Landscapes, Thriving Communities:

Achieving a Collaborative Vision of the Future

2018 Regional Collaborative Workshop

Co-hosted by the Idaho Forest Restoration Partnership

and the Montana Forest Collaboration Network

[object HTMLImageElement]

Coeur d’Alene Resort, Coeur d’Alene, Idaho

March 20-21, 2018

Writing in The Common Law, a book of essays he assembled in 1881, Associate Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., described the myriad social and cultural underpinnings of the nation’s legal system:

“The life of the law has not been logic,” he wrote. “It has been Experience - the felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, institutions of public policy, avowed or unconscious; even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men have had a good deal more to do with the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of the nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.”

Justice Holmes’ insightful description of the great unseen forces that have shaped and reshaped our society came a mere 17 years after our nation’s conservation movement first took shape. That moment came in 1864 – the year before President Lincoln was assassinated, the year that Sherman and his army of 112,000 crushed the Confederacy in their long march to Atlanta, and the year in which George Perkins Marsh published Man and Nature, a book many consider the anthem of early conservationists, one in which the scholarly Marsh successfully challenged the myth that earth’s natural resources are inexhaustible. Gifford Pinchot called _Man and Nature “_epoch making.”

I’m about a year into a history of our country’s conservation movement. It began as a lecture I gave last April to a forest policy class at the University of Idaho. I’m currently navigating 1947, the year the federal timber sale program got rolling under the aegis of the Truman Administration and two of its most able strategists: Crowe Girard Davidson, a politically shrewd Louisiana lawyer who was one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s favorites, and Daniel L. Goldy, a brilliant but often acerbic economist I knew well, who, after seeing Oregon’s coast range for the first time in 1946, concluded that the vast timber resources held in the West’s largely inaccessible National Forests constituted the only economic engine our country had that could power our economy’s transition from wartime to peacetime footing.

If the GI Bill and the nation’s post-war homebuilding boom are the measures, Goldy was right

The history of what happened between the publication of Marsh’s book and the beginning of the post-war federal timber sale program traces the felt necessities that Justice Holmes described so eloquently in The Common Law.

From hijinks to high drama, from cowardly deeds to deeds of great courage, from birthday surprises to death threats, from political chicanery to political genius: the story of conservation’s advance is fascinating and instructive.

I can’t write the last chapter in my story because the events that will shape it haven’t happened yet - and that is why I am here this morning. This un-lived history lends shape and substance to your hope-filled collaborative vision. It is yours, and yours alone, and only you can bring to life.

The optimist in me thinks that the resilient landscapes and thriving communities you envision will someday twinkle like bright stars in the night sky. You will have put them there, and their brilliance will illuminate the very difficult work you have embraced:

I am a journalist by profession. I have been writing for money for 57 years. I am a dinosaur from another time, long before the Internet or cell phones or even FAX machines. The first newspaper that hired me bought its national and international news from Associated Press and United Press International. It arrived on a land line connected to a teletype machine that made so much noise that our news editor had it enclosed in a Celotex-insulated box the size of a washing machine crate.

Over five-plus decades, I have covered every imaginable news story: Junior Miss Pageants, murder trials, city council meetings, autopsies, gubernatorial speeches, parades, horse races, fatal car wrecks and Presidential inaugurations, but for the last 32 years, the nation’s forests have been my beat: private, county and state-owned forests, tribal forests and forests owned by the federal government.

Early on, I was so taken by the enormity of the story that I decided the only way I could do it justice was to start my own magazine. With some venture funding from a group of southern Oregon lumbermen, I published the first edition of Evergreen Magazine in the fall of 1986. We are still at it, still publishing in print, though those who helped us get started are long dead, and now we also run a huge website that has become my bully pulpit, and the repository of 32 years of research and writing.

The big events have been:

Clarke-McNary put the Forest Service in the fire-fighting business alongside privately-funded fire cooperatives that had been formed in Oregon, Washington and Idaho following the 1902 Yacolt Fire, which ravaged a half-million acres of old growth timber in southwest Washington and northwest Oregon, much of it owned by the old Weyerhaeuser Timber Company. The first cooperative was at Potlatch, 70 miles south of here.

President Coolidge signed Clarke-McNary into law on June 7, 1924. I mark this date – nearly 94 years ago - as the beginning of the nation’s hard-fought but increasingly expensive, dangerous and failing effort to stuff the Wildfire Genie back in her bottle.

Greeley, who was then the third Chief of the Forest Service, overcame what he called his “terrible New England conscience” by hiding in the Senate Cloakroom and slipping loaded questions of Senate members who supported Clarke-McNary’s passage.

Greeley was Chief Forester for District 1, and was based in Missoula, Montana at the time the Great 1910 Fire swept over three million acres in northern Idaho and western Montana, and it was he who supervised the gruesome task of burying the remains of 87 firefighters who had been burned alive in became a firestorm driven by hurricane-force winds.

The tragedy so traumatized Greeley that he dedicated the rest of his professional life to – as he said – “running smoke out of the woods.”

I was just as brazen as Greeley where HFRA was concerned: I put together a series of colorful bar graphs displaying gross growth, mortality, net growth and harvest in National Forests in Idaho, Montana and Washington.

The charts, which were used in House floor debate, have since been updated, and appear on our Evergreen website. They quantify the precipitous decline in the health of the West’s National Forests. As you know, mortality now exceeds growth in some western National Forests.

I also published two, eight-page photo essays under the Evergreen masthead. The front-page headline on our July 2003 report asked if the fire-ravaged stream pictured on the cover would be the U.S. Senate’s environmental legacy.

On the August cover, I boldly asked if anyone could explain to me the federal government’s forest management objective. Among the before and after pictures: Fire-killed timber in New Mexico and Arizona; bug-killed trees here in Idaho and California; the beautiful western larch thinning that graces your program cover; and John McColgan’s epic photo of elk huddled in the East Fork of Montana’s Bitterroot River, surrounded by wildfire. I hope they made it to safety

My plea for an explanation of our nation’s wretched forest management policy went unanswered, and I was assuredly not at my journalistic best, but by 2003 I had published 11 editions of Evergreen that featured wildfire pictures on the cover. Dead and dying forests had also graced three covers - the earliest a 1989 report titled, “Grey Ghosts in the Blue Mountains.” By then, eastern Oregon’s Blue Mountains were infested with bark beetles, and the color grey was fast replacing green on hundreds of thousands of acres.

Little did anyone realize that the ecological disaster that was unfolding west of LaGrande, Oregon would - in a scant 20 years – overtake some 90 million acres of National Forest land in the West, an area nearly as large as Montana, our fourth largest state.

Until all of you showed up in this story, there had not been any good news to report. Now there is. In fact, the story of the National Forest restoration work that you are doing in concert with the Forest Service here in the Intermountain West is the most significant good news story I have covered in my 57 years as a working journalist.

I confess a well-honed bias where you and your tireless dedication are concerned. I admire your courage and creativity, your energy and your willingness to trudge on, even when you aren’t sure where the less-traveled road you are on will take you next.

In the long history of conservation, nothing like what you are doing has ever been done before. Let’s face it: the often-self-centered Gifford Pinchot was lucky as hell. He had Teddy Roosevelt in his hip pocket. You’re lucky to have gas money!

And yet – and yet – you look to me like the “get out of jail free” card Congress and the U.S. Forest Service have needed for some time now. The “Jail” in this case is the regulatory minefield Congress created that the Forest Service has been trying to navigate since the 1970s. It has not gone well for the beleaguered agency, or for forests in its care.

Until you got your wheels beneath you, serial litigators ruled the roost. Not so much now. Increasingly, federal judges are nodding their approval of your hard work and exceptional attention to detail. And why not? They read the same newspapers we read, and they breathe the same carcinogenic wildfire smoke the rest of us breathe for most of the summer.

You are protecting much more than trees. You are protecting an emerging lifestyle that blends rural and urban culture and values: clean air, clean water, abundant fish and wildlife habitat and a wealth of year-round outdoor recreation opportunity.

From the 40-some collaborators we have interviewed over the last three years, we know that many of you have been at this table for a long time. Several of you have confided that you are worn out. That’s understandable, but you can’t quit yet. First, you must recruit and train the generations of younger men and women who will follow in your footsteps.

Pardon my pun, but the woods are full of young people who love forests and nature and are looking for ways to live meaningful lives in our increasingly mean-spirited world. Some of them aspire to be foresters or biologists or botanists of one kind or another; others just want to get the hell out of Dodge. My step-son, who runs our website, thinks he’d like to be a fishing guide someday. The further off the grid Eli can get, the happier he will be.

Surely, this multi-generational bonanza holds all the new recruits you will ever need.

From my journalistic travels, I can tell you that most Americans are anxious to hear your good news story, because it is uplifting and inspiring and filled with anecdotes about the wonderful things that happen in our society when people from disparate walks of life and points of view reach across the aisle to one another, join ranks and march forward arm in arm in hopes of achieving something more hopeful, more powerful and more useful than anything they could ever possibly achieve on their own.

Your collaborative successes speak to the disarming majesty of your selfless journey – answering the felt necessities of our time.

Justice Holmes summed up those necessities in a single word: Experience. Remember that word. It is the sum of all that you have learned and done by being very patient with one another.

Justice Holmes said something else about experience that I think quite appropriate this morning. He had fought in the Civil War with the 20th Massachusetts Regiment, and had been badly wounded at Antietam, where more than 22,000 were killed or wounded, and at Chancellorsville, where he was left for dead among the 10,000 who did die.

Reflecting on his Battlefield Experience, Justice Holmes shared these inspiring words with his Band of Brothers in a Memorial Day speech to veterans gathered at Keane, New Hampshire on May 30, 1884:

“We have shared the incommunicable experience of war. We have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top. In our youth, our hearts were touched with fire.”

I have no doubt that many of your hearts have been touched by fire in the years that you’ve worked to build the kind of trust and honest dialogue it takes to start a collaborative, hold it together and keep it going and growing.

As your principal storyteller, I too have felt this passion for life to its top; and for some time now, I have been thinking about how we might together share our seemingly incommunicable experiences with publics that want to hear and understand your collaborative story – and I think I have found it.

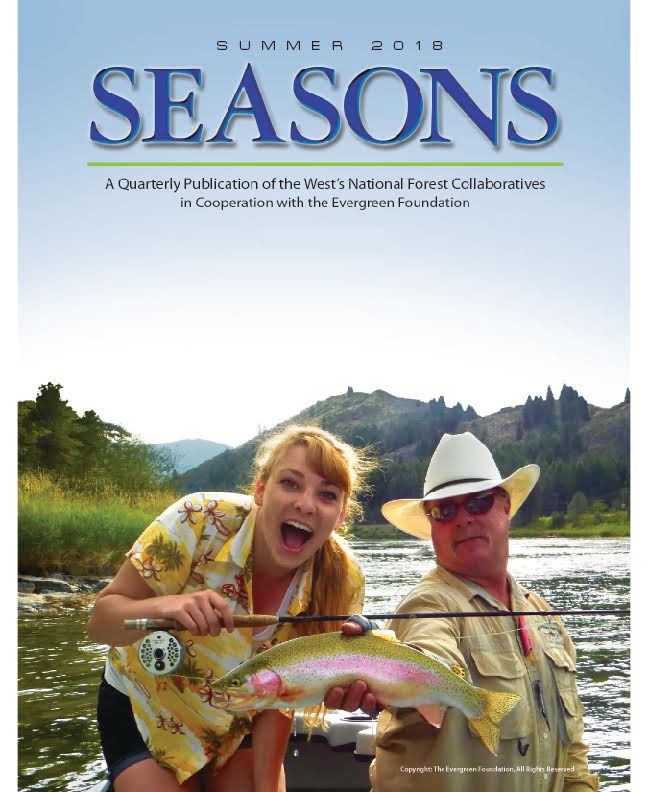

I realize this is a lot to absorb in a half-hour, which is why we have a sample SEASONS cover, which we have copyrighted, for you to consider and discuss with us. That’s our daughter on the cover. It was her first fly-fishing outing – and she out-fished me!

We think SEASONS is the image and likeness you need to market yourselves to critically important target audiences that can help you be more successful.

The “what ifs” I have enumerated are real, and the restoration projects you envision have the potential to power the greatest revolution in the history of federal forestry.

The smaller diameter logs that your projects are providing to family-owned sawmills here in the West are driving unprecedented advances in engineering, architecture and wood product manufacturing technologies. Cross-laminated timbers and mass plywood panels are taking the building industry by storm. Not since the invention of plywood, which debuted at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland in 1905, has an event of such magnitude occurred.

Thanks for inviting us to be here with you at your 2018 convention. In our glass-half-full world, these are exciting times.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.